Tag : News

Clipperton releases today its Cybersecurity Market Monitor 2025. Building on last year’s edition, this report analyzes the valuation landscape in the cybersecurity space, covering public market performance, transaction activity across Europe and North America, and the emerging themes shaping the sector.

Cybersecurity Software: Resilience in a Polarized Market

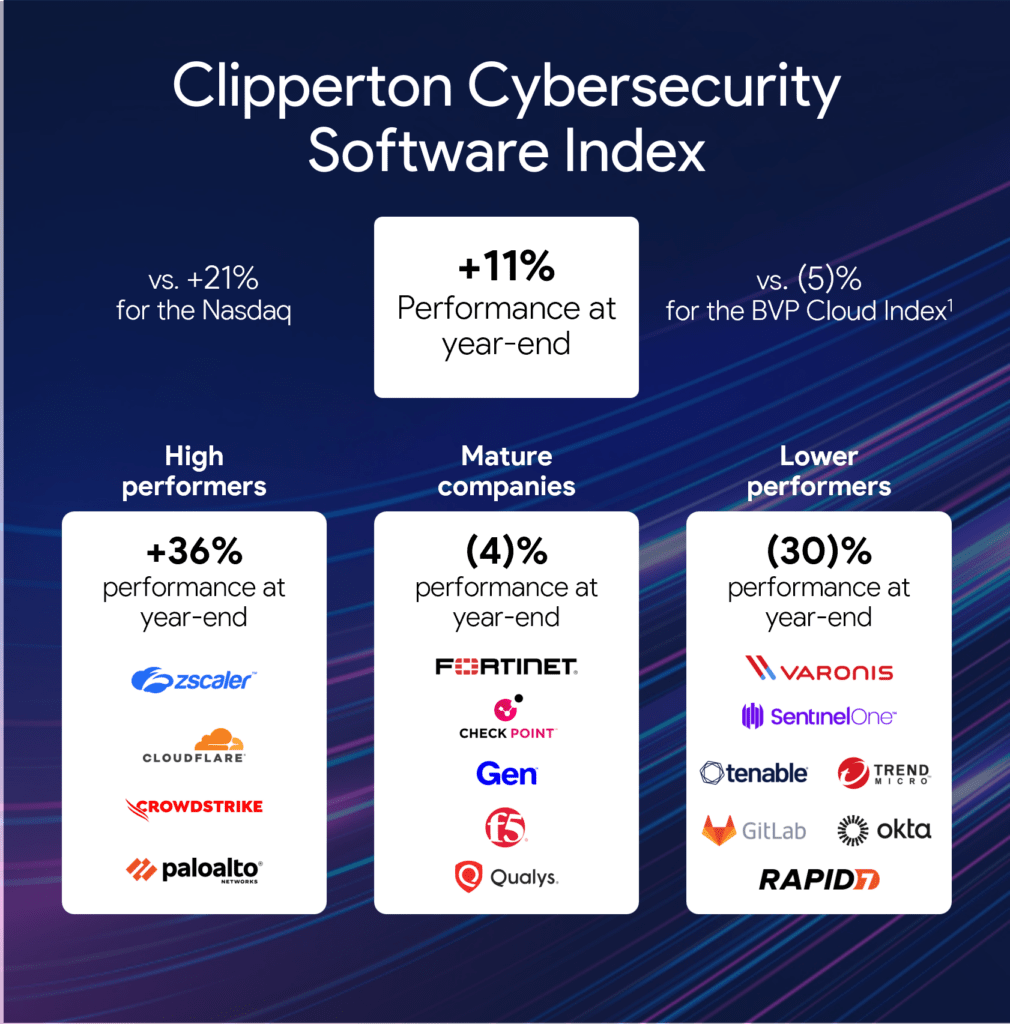

The Clipperton Cybersecurity Software Index delivered a resilient +11% return in 2025, outpacing the BVP Emerging Cloud Index (-5%) while trailing the NASDAQ (+21%). This relative lag reflects the broader software slowdown: as enterprise software deployments cool, demand for incremental security seats and new workload protection naturally follows suit.

The year was defined by sharp market polarization. Our analysis categorizes the cybersecurity universe into three distinct archetypes, each reflecting a different relationship between growth, profitability, and market sentiment:

- High Performers: Cybersecurity leaders with a Rule of 40+ profile, combining hyper-growth with scalable profitability (e.g. Cloudflare, Crowdstrike, Palo Alto Networks, Zscaler): +36% in 2025, trading at a median 18.5x EV/Revenue;

- Mature Companies: Established players prioritizing high EBITDA margins (>35%) over top-line expansion (e.g. Fortinet, Check Point, Qualys): -4% in 2025, valued at a median 14.1x EV/EBITDA;

- Low Performers: Vendors undergoing operational or strategic transitions, with decelerating growth and compressed multiples (e.g. SentinelOne, Okta, Trend Micro): -30% in 2025, at a median 4.5x EV/Revenue.

Outlook 2026: The Strength of Platformization

The early weeks of 2026 have put the broader software market under significant pressure, with the enterprise software index down over 26% year-to-date. Against this backdrop, our cybersecurity index is down approx. 15% over the same period. This resilience is most pronounced among leaders such as Palo Alto and CrowdStrike, which benefit from genuine “cyber platform” status and high switching costs.

Download and read our full analysis for deeper insights into the key trends shaping the cybersecurity investment landscape.

Authors: feel free to reach out to discuss these insights:

- Thibaut Revel, Managing Partner

- Richard Hooper, Managing Partner

- Dr. Nikolas Westphal, Managing Partner

- Olivier Combaudou, Partner

- Pierre Pinsault, Associate

- Jérémy Vignola, Analyst